This Irish pickaxe is the heaviest one I’ve ever lifted. Old too. I’m out behind a barn on the southwest coast of Ireland, on a farm, borrowing tools from a friend to dig a hole. The shovel has a piece of blue tape around the handle just above the metal spade. I ask the farmer, Con Burns, what the tape is for. He explains that sometimes he goes to a funeral and has to dig a grave with other men. Things can get a little confusing later after the digging is done. Tradition dictates that the shovels can’t be brought home right away and must be left laying across the grave until the next day. The blue tape tells him which shovel is his.

My plan is to dig a hole on Rabbit Island, a few hundred yards off the coast. I’m told there are no rabbits left on the island. No people live on the island, there are no houses, no roads, just a few square kilometers of wild green rolling fields, a couple ivy choked stone ruins, rocky beaches and wind.

A group of us head out in a small boat and two kayaks and I quickly leave our picnicking gang on the beach. I am drawn to the high ground, nearly hopping with anticipation, eager to find my spot and dig. Without a word Finbar, a nineteen year-old Englishman raised just a few miles from Rabbit Island, falls in behind me and we scramble up a cliff-side trail. This collaboration wasn’t planned, but I need help, and he has excellent wingman potential.

I’ve known Finbar, and his younger brother Ewan, since they were small boys. A dozen or so years ago I was exploring on Rabbit island with a version of this gang and I ended up with young Finbar, just the two of us, checking out a ruin while the rest of the group played on the shoreline. I was doing something, examining a stone and Finbar gazed up at me, studying my troubled expression. He looked, amused, then confused, and he asked innocently in his thick English accent,

“What’s that strange face you’re making?”

Nobody had ever asked me that before.

It seems I make a strange, spastic wincing face when I am concentrating. I always have. I don’t seem to have any control over it and I don’t think I ever will.

Finbar is now a strapping six foot four and no longer even remotely alarmed by my odd facial expression. He has a top-knot of black hair, keeps the sides of his head shaved, and a gauge in one ear. He also has a nice camera and he strikes me as calm, soulful, and quite keen on helping me document this Irish hole.

The sun is warm and muted behind thin clouds. We walk through waist high grass, bracken and flowers, purple thistle and green stinging nettles. They don’t penetrate my suit pants. My crawl boots are quickly soaked from yesterday’s rain, still wet in the shadowy depths of vegetation. Finbar asks questions about the origin of Hole Earth and the conversation ranges easily as we move along. The ground has a gentle give, a bouncy living mattress of tangled lush turf. The scent is fecund electric. I feel altered, like the Oz scarecrow in a field of poppies. But I’m far from tired. The wind gusts again, bending the blades of grass, bouncing the flowers around, feathering the surface of the sea. My suit feels amazing. A better action outfit has yet to be invented.

After some speculation about location we head for the high spot on the island, a hill overlooking the entire universe. I start to dig but the shovel can’t cut the thick grass. This will require hands, at least at first. On my knees I tear out the mattress of bouncy wet interwoven grassy weeds and flowers with my bare hands. The scent is wild, intoxicating, intensely sweet, even in the gusty wind. Finally I expose the earth.

Lifting and swinging the heavy pickaxe is hard work. When it hits the ground the reverberation impact jangles my arms and torso. This is not going to be short or easy. This hole will be as hard as the place is beautiful. I have no gloves. Blisters are waiting.

I gouge maybe half a foot down and stop for a second. The soil is tougher with every swing of the pick. This is tight compact earth bound together with flecks and shards of shale and tiny roots. I’m meeting serious resistance. I feel like I’m trying to break open a city street. Damn. It all seemed so soft and inviting at first.

Then a strange blessing occurs. My shovel snaps off, right at the blue tape, right where the handle meets the spade. I settle back on my haunches and stare at my broken tool. The shovel is history, at least the handle part. I ponder the shovel’s story. How many real human graves did this shovel fill or dig before one freaky Yank hole digger came along and broke it? I remove the blue tape from the handle and slip it in to my suit jacket pocket.

My wingman takes pictures and wears his camera and mine around his neck. I chuckle and shrug, disappointed and somewhat relieved by the shovel situation. Finbar is amused and respectful. He offers to go back to the mainland and find another shovel. That would take an hour at least. I can’t make a hole without a proper shovel. Hacking away with just the metal spade is not an option. The pickaxe alone won’t do the trick. I suppose, if my life depended on it, a hole could be achieved with what I have left. But right now my life depends on sitting back for a moment in awe. From our vantage point we gaze out at the waves of green moving in the wind. The sky roars with the ocean.

It is time to improvise. No shovel means no hole. I release myself from the task at hand. I tell myself--- this isn’t giving up--this is letting go. I feel a tinge of guilt, but the island has things to show us beyond the digging. There is more than one way to enter this place.

An alternative holy path appears—I find myself at the edge of a cliff, waves far below crashing into jagged towers of stone—I discover a round grassy bowl, just my size, waiting for me, and I curl up, fetal inside the island’s glorious green mane. We wander on and without warning I stop, drop to my knees, and pitch forward, face down in the garden of Eden.

Eventually we make it down to the beach where we explore stone formations. We observe our surroundings in a reverential state, still in the spirit of Hole Earth.

I tell myself again, the shovel broke, nothing could be done, let it be. I reach into my pocket and touch the gravedigger’s blue tape.

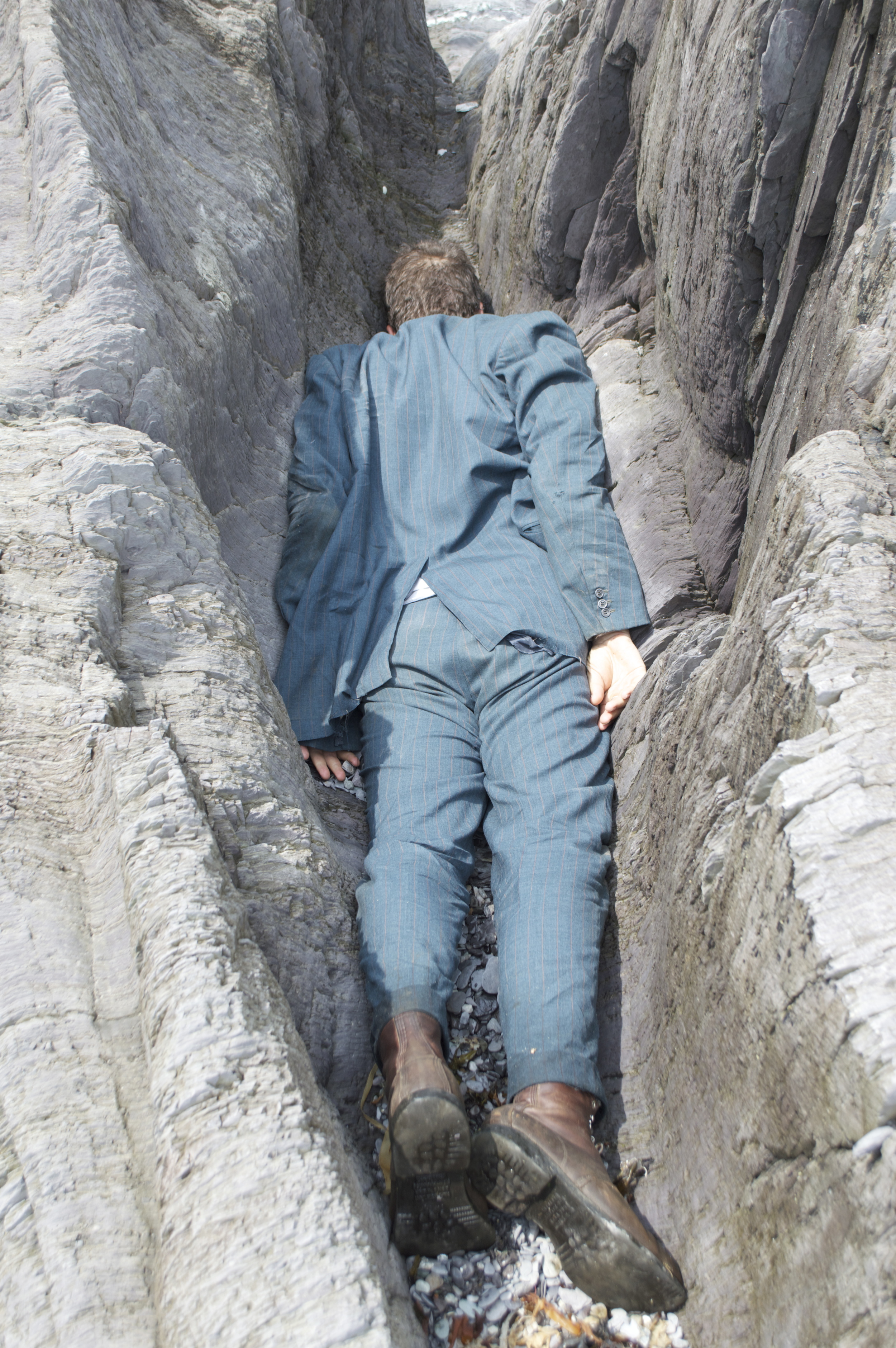

Did I give up too easily? But I don’t want to toil and dig and cut a hole into the face of this place. But that was the plan. To distract myself from this line of thinking I slow motion face plant into stone and stay that way, making stories in my mind. I am a corpse, a dustbowl drifter sleeping off a drunk, a businessman who has fallen from a great height.

Eventually I curl up tight inside a rounded stone formation by the water and I listen to the waves. They slosh and hiss, approach and recede, over and over again. How long has this sound been going on? I can’t begin to fathom. I try to match my breathing to the rhythm of the waves and then I hear human voices. The rest of our group has located us. I stay where I am and wait as they climb down a low cliff trail and come closer. They will find me here.